The Mysterious Origins of Debit and Credit

One chilly day in the Pacific Northwest, a helicopter pilot searched for the helipad on a sprawling snow-covered corporate campus. Hovering above a large parking lot, he saw an employee walking towards an entrance. The pilot swooped down and called to him for help, asking, “Where am I?”

The employee replied, “In a helicopter.”

Though technically correct, the answer is not helpful (except giving the pilot proof that he was at the tech support building), which is why this joke typically gets a laugh. Sadly, when it comes to understanding the words debit and credit, the definitions in Accounting books bear a striking resemblance to this “helicopter” response. Financial Accounting, Twelfth Edition, Glindex says:

Credit. The right side of an account.

Debit. The left side of an account. (Thomas, 2018)

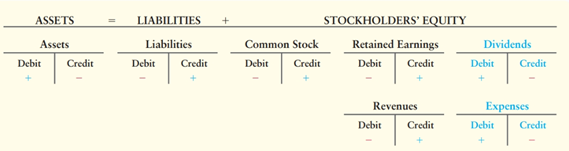

If these terms only meant left and right, we would call them left and right. But these are shorthand for their complete definitions, which, as it turns out, entail a chart of rules.(see Figure 1) This is because the actions of debiting and crediting change based on the type of account and the transaction (Thomas, 2018).

There are four possibilities:

- a debit to a debit account increases its balance

- a credit to a debit account decreases its balance

- a debit to a credit account decreases its balance

- a credit to a credit account increases its balance

Using two words to describe four things seems reckless for a field that relies on accuracy. Today, the English language offers 171,146 words to choose from, plus another 47,156 words considered obsolete. (OED Online, 2022) Considering the wealth of word choices, there are better options for communicating transactions more clearly. At a minimum, they could use prefixes to create novel words like updebit, dedebit, upcredit, and decredit, and that might eliminate the need for a chart to decipher what a word means. And on that note, why do they also use the two words used as adjectives, nouns, and verbs?

One might assume it has to do with common root words. They come from Latin roots: debito means what is owed to, and credito means owed by. (Geijsbeek, 1914) But assets are debit-balance accounts, plus paid-in capital and revenues are credit-balance accounts (Thomas, 2018) so at first glance, the Latin roots do not appear to align. In an article for the Accounting Historians Journal, Vahé Baladouni concluded, “While form is there, the threads of meaning are not; or to put it somewhat differently, the etymological significance of these words has faded away.” (Baladouni, 1984)

Granted, understanding why words changed their meanings is not necessary to learn accounting today any more than binary code prowess is required to work in IT. However, we can use those words like breadcrumbs to take us through the books of the past to find answers to the questions above and other things that are otherwise lost to us today.

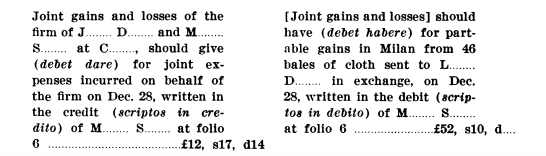

Foundations in Italy

Today’s bookkeeping practices go back to Italy in the 1200s. We can see remarkable similarities to bookkeeping today in the 1297 books of merchants Rinerio and Baldo Fini, such as accounts assigned to things and not just people. (Brown, 1905) Figure 2 shows an excerpt from a ledger from Milan dated 1396 and a clue to today’s mysterious word choices. Their entries, translated into English, include the phrases should give and should have. They do not use the terms credit and debit to describe the action as they would in English today. They use the terms debito and credito referring to where the transaction is recorded. (Littleton A.C., 1926)

In Venice in 1494, Luca Pacioli synthesized nearly two hundred years of Italian bookkeeping practices in his book, De Computis et Scripturis. (Brown, 1905) He calls the systems of the Italian bookkeepers the “debito and credito” method. However, as was the practice for hundreds of years, he uses the Italian words dee dare (shall give) and havere[1] (shall have) to describe the actions we know today as debit and credit. (Littleton, 1926)

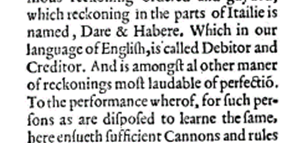

Hugh Oldcastle translated Pacioli’s book to English in 1548. Unfortunately, this first edition is no longer in print. However, John Mellis printed a second edition in 1588, and from this, we can see how Pacioli’s book was translated to English.

Mistranslation One

In chapter 15 of his book, Pacioli provides a sample entry translated into English today as “Cash shall give (dee dare) on November 8 per capital.” (Geijsbeek, 1914) In comparison, Oldcastle and Mellis provide the translation of entries such as:

Aug. 8 – Chest or Ready Money ought to give me (or is Debtor[2] to Stock) £, s, d for so much ready money in gold and silver I have this day in stock, as in credit, folio….£, s, d (Littleton A.C., 1926)

They give the literal translation, “ought to give,” but in parentheses, they add “is Debtor to Stock.” This seemingly minor choice will cause confusion for hundreds of years. A.C. Littleton, a CPA, author, and expert on the history of accounting, explains, “In this phrase, Mellis is unwittingly laying the groundwork for the inept English terminology of the future, which makes it necessary to use the same word debit as a noun, verb, and adjective.” (Littleton, 1926)

Mistranslation Two

Oldcastle and Mellis took a phrase that meant to give and translated it as one who owes (debitor). They also took a phrase that meant to have and assigned a term (creditor) that means one who owes. (Oldcastle & Mellis, 1588) (OED Online, 2022)

Mistranslation Three

In an explanation of double entries from Pacioli’s chapter 14 below, he used four distinct words that mean to have, giving, debitor, and creditor.

For each one of all the entries that you have made in the Journal, you will have to make two in the Ledger. That is, one in the giving (in dare[3]) and one in have (habere). In the Journal, the debitor (debitore) is indicated by per, the creditor (creditore) by a, as we have said. In the Ledger, you must have an entry for each of them. (Geijsbeek, 1914)

As noted above, Oldcastle and Mellis assigned the words creditor and debitor to mean have and giving. When writing the English version of passages like that above, they must also translate the Italian word debitore as the English word debitor and the Italian word creditore as the English word creditor. From this point forward, what was supposed to be four words will be described in English by two words: debitor and creditor.

English Variance

While debitor and creditor were changing in the English language, other languages continued to express more of a literal translation of the Italian words. (See Table 1)

| Table 1. The Evolution of Bookkeeping Verbs | ||

| Language | Left-Side | Right-Side |

| English | debit (owes) | credit (trusts) |

| French | doit (should) | avoir (have) |

| German | soll (shall) | haben (have) |

| Italian | dare (give) | avere (have) |

| Spanish | deber (give) | haber (have) |

| (Littleton, 1962) | ||

During this era, in the 1600s, the word credit meant to trust in English. For example, in 1695, John Locke explained “credit being nothing but the expectation of money within some limited time.” (Locke, 1695) If we think about credit as trust, we understand why liabilities are credit-balance accounts today, especially with a reexamination of the term liability. (Geijsbeek, 1914)

During this era, the word liability was not a word yet, and it would not be until 1794 that it was introduced as a legal term. (OED Online, 2022) Liabilities are not technically due at the moment the financial statement is reported, so the company is not liable at that moment, which means liability is not the best choice of words. Rather, the entity that will be owed in the future has trusted the company to repay them later. (Geijsbeek, 1914) From this perspective, liabilities are like revenues and paid-in capital in that they are resources that other entities have entrusted to the company. So, even though English employed a different meaning than other languages, it was still an accurate description of these accounts. In the 1700s, the term credit took on more of a technical meaning in finance and accounting. (OED Online, 2022)

Dutch Advancements

Simon Stevin, a mathematician, civil engineer, and civil servant from Holland, ushered in a new, modern era of accounting and bookkeeping when he published his book in 1608. (Littleton, 1926) Stevin was a gifted mathematician who was the first to convert fractions into decimals. His inventions, such as improvements to canal locks for waterways, make him widely considered a father of modern engineering. He transformed the detailed journal entries of the past into streamlined phrases like “Cash debit per Pieter.” (Geijsbeek, 1914)

One of the most insightful authors on the Dutch innovations to the Italian bookkeeping method is John B. Geijsbeek. Geijsbeek was a CPA, attorney, and chair of the American Association of Public Accountants (Boston Herald Staff, 1912) who immigrated from Holland to the U.S. in the late 1800s. As a native Dutch speaker who studied business in Holland before his career began in the U.S., he was uniquely positioned to translate the Dutch accounting and bookkeeping texts of the 1530s – 1610s. His book, Ancient Accounting Principles, provides insight into the principles included in the Dutch originals and the meaning lost when translated into English. For example, Geijsbeek explains how Stevin applied the algebraic formula to achieve streamlined entries. He gives the example of an entry in long-form:

“Cash debit to myself — proprietor credit — for the money I gave the cash drawer for safekeeping,” and “Myself debit to Peter Credit—he gave me money which I may have to return to him if he does not owe it to me.”

Because the amounts to and from myself would be equal, the Dutch found that both can be eliminated using the algebraic formula as in “a=b; b=c; hence a=c,” as illustrated in Figure 4 below. (Geijsbeek, 1914)

| Figure 4. Algebraic Formula Applied to Bookkeeping Entries | |||||

| A | = | B | B | = | C |

| Cash Debit | to | Myself Proprietor Credit | Myself Debit | to | Peter Credit |

| For the money, I gave the cash drawer for safekeeping. | He gave me money which I may have to return to him if he does not owe it to me. | ||||

| Note: Strikethrough shows how two equal amounts to and from “myself” can be eliminated using the algebraic formula A=B, B=C, so A=C. (Geijsbeek, 1914, p. 15) | |||||

“Directly and indirectly, Pacioli through the Dutch has laid the foundation of our present accounting literature and our present knowledge of bookkeeping,” Geijsbeek says. (Geijsbeek, 1914) Unfortunately, much of the knowledge and concepts were lost in the English translation by Richard Dafforne.

Richard Dafforne was an English schoolmaster who loosely translated his “good friend” Stevin’s work into English in his 1636 book, The Merchants Mirrour. (Dafforne, The Merchants Mirrour 2e) However, he does not convey Stevin’s logic and reason, including the algebraic formula above. (Geijsbeek, 1914) While Stevin uses the Latin terms debet and credit, Dafforne follows Oldcastle and Mellis’ translation strategies, such as using nouns in place of verbs and reframing the entries from giving and having to being about who owes and who is owed, respectively. (Geijsbeek, 1914) Unlike Oldcastle and Mellis, Dafforne does not include the literal translation of the words. (Littleton, A.C., 1926)

Dafforne’s language is decorative to the point of being unclear when explaining the basis for the shortening of entries. Table 3 below contrasts Dafforne’s and Stevin’s explanations about making cash the debit(or).

Table 2. Comparison of Explanations

| Stevin (translation) | Dafforne |

| “Suppose that someone by the name of Peter owed me some money, on account of which he paid me £ 100, and I put the money in a cash drawer just as if I give it the money for safekeeping. I then say that that cash drawer owes me that money, for which reason (just as if it were a human being) I made it a debtor, and Peter, of course, becomes a creditor because he reduces his debit to me. This I put in the journal thus: ‘Cash debit per Peter.'” | “Because Cash (having received my mony into it) is obliged to restore it again at my pleasure: for cash representeth (to me) a man, to whom I (only upon confidence) have put my mony into his keeping; the which by reason is obliged to render it back, or, to give me an account what is become of it. Even so, if Cash be broken open, it giveth me notice what’s become of my mony, else it would redound it wholly back to me.” |

| (Geijsbeek, 1914) | (Dafforne, The Merchants Mirrour, 3e, 1660) |

“In spite of his quoting so freely from Stevin and coming so near to what Stevin says, Dafforne has failed entirely to transfer to posterity the idea of the real reason for a double-entry or two debits and two credits,” Geijsbeek says. The closest Dafforne comes to explaining the purpose of double entries is that cash, merchandise, and all possessions are “but members of that whole body (stocke); therefore, by the joint meeting of all those members, the body (stocke) is made compleat.” (Geijsbeek, 1914)

“Through the entire book, always ‘how’ but never ‘why’ — the very opposite of Stevin,” Geijsbeek says. Littleton concurs, “The translation of early bookkeeping works from the Italian into Dutch and English failed to carry over the real essence of transaction analysis which lay within them.” (Littleton, 1926)

“Through Dafforne’s faulty transfer of the bookkeeping ideas of the Dutch authors into the English language, we have lost the very essence and foundation of the theory of bookkeeping,” Geijsbeek says. “Anyone reading Stevin first and then Dafforne will have no trouble in arriving at this conclusion. It is like the reading of a letter from an experienced old man, followed by the treatment of the same subject by a high school student.” (Geijsbeek, 1914)

Dafforne’s book’s popularity eclipsed previous English language books about bookkeeping, prompting updated editions published in 1651, 1660, and 1684. “It is to be regretted that in the transfer of the expositions of the theory from the Dutch language (as so plainly exemplified by the scholar Simon Stevin ) to the English (by the flowery schoolmaster Richard Dafforne) should have been so badly done that all records of the scientific part of the art and theory have been so completely obscured.” (Geijsbeek, 1914)

Debitor and Creditor Become Debit and Credit

Mellis’ verb-free preferences in the 16th century left a gap, and, as we often do in the English language, we made verbs out of nouns. In 1682, debit and credit made their official English debut as verbs in the accounting sense. (OED Online, 2022) The terms debitor and creditor, as in the names of the sides of accounts, also transform, and they eventually lose their -or suffixes. We can see this transformation through examples such as Vernon’s Complete Comptinghouse, published in 1678, which uses the terms debit and credit (OED Online, 2022), whereas Dafforne would have used debitor and creditor.

English bookkeepers had been abbreviating debitor as dr and creditor as cr since at least 1633 (Sherman, 1986). These abbreviations were picked up as the headings on accounts in the 18th century. (Littleton, 1926) The Scales of Commerce and Trade; and Architectonice, published in 1660, makes the last reference to a debitor account. The term debitor continued to be used until at least 1795 but was replaced by debtor making debitor obsolete today. (OED Online, 2022) The word creditor continues to be used today, though its last published use to describe the right side of an account was in the Journal of American Bankers Association in August 1916. (OED Online, 2022) Although the right and left columns are no longer called debitor and creditor, the abbreviations for debit and credit remain as dr and cr, respectively. (Sherman, 1986)

Other Befuddling Terms

Perhaps nothing confuses an accounting student more than starting their first semester with knowledge of a debit card. After hearing phrases like “Visa® Debit Card is an easy, secure way to pay directly from your checking account” in commercials (Avadian Credit Union, 2022), students and most consumers might believe debit refers to the deduction from their checking account. However, the debit refers to the payment to the merchant and banks receive. (Hayashi, Sullivan, Weiner, 2006) Debit cards have been around since 1966, when the Bank of Delaware piloted the first debit card program. (Hayashi, Sullivan, Weiner, 2006) In December 1974, the Comptroller of the Currency issued a ruling that Electronic Funds Transfer terminals located off-site of a bank are not branches and could be installed virtually anywhere in the U.S. In 1975, national bank credit card organizations announced a new type of card, which included consumer-centered names such as Check Card, Plastic Check, Handi-Check, and Asset Card (Little, 1975), but the name that stuck was the merchant-centered term debit card.

Working in tandem to befuddle new accounting students is a phrase they might have heard from a business: “We’ll credit your account” (Nationwide, 2022), which consumers recognize as “funds are going into your account.” From this understanding, they might logically conclude that credit means an increase in general. However, the business uses the word credit, referencing its own records and chart of accounts.

Conclusions

So much of what is confusing about accounting terms is the result of poor language translations over four hundred years ago. Over hundreds of years, the Italian merchants created a scientific system that remains in use today. (Littleton, 1926) The Dutch transformed Italian accounting and bookkeeping by streamlining entries. (Geijsbeek, 1914) Unfortunately, much of the reasoning, algebraic principles, and concepts expressed in the work of Pacioli and Stevin were lost through poor English translations and less gifted authors of accounting and bookkeeping instruction during the 1500s and 1600s. (Littleton, 1926)

“It must be admitted that if we today would abolish the use of the words debit and credit in the ledger and substitute therefore the ancient terms of ‘shall give’ and ‘shall have’ or ‘shall receive,’ the personification of accounts in the proper way would not be difficult and, with it, bookkeeping would become more intelligent to the proprietor, the layman, and the student,” Geijsbeek concludes. (Geijsbeek, 1914)

Although the terms debit and credit as we know them today are unlikely to change, for centuries, accounting and bookkeeping teachers have found ways to overcome the deficiencies in the language of accounting. So, although knowing the original concepts behind today’s accounting and bookkeeping terminology is not required to learn the principles of accounting, there is immense value for those students who ask, “Why is it that way?” There is also insight and utility in this knowledge, as Geijsbeek explains:

With the aid of ancient terms, we can read intelligently and explain the abbreviated forms used in bookkeeping so that it becomes at once apparent why accounts like the cash account, which to the uninitiated looks like proprietorship, can be shown on the debit side of the ledger and why capital account, which always represents ownership, appears on the credit side. This, at first thought, may seem contradictory, but the reason for this apparent inconsistency lies in the elimination (through bookkeeping ) of equal terms ( as per rules of algebra ) brought about by the theoretical making of double entries (two entries, each with a common debit and credit) and thus abbreviating it beyond the interpretation of ordinary language. (Geijsbeek, 1914)

[1] During this era, the letters b and v are often interchanged, so habere appears here as havere.

[2] During this era, English debtor and debitor were used interchangeably. (OED Online, 2022)

[3] In this passage, the words Pacioli used are in parentheses.

Works Cited

Avadian Credit Union. (2022, May 10). VISA Debit Card. Retrieved from Avadian Credit Union: https://www.avadiancu.com/Personal/Build/Personal-Checking/VISA-Debit-Card

Baladouni, V. (1984). Etymological Observations on Some Accounting Terms. The Accounting Historians Journal, 11(2), pp. 101-109.

Boston Herald Staff. (1912, December 23). To Train Men for Efficiency. The Boston Herald, p. 7.

Brown, M. J. (1905). A History of Accounting and Accountants. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack.

Dafforne, R. (1651). The Merchants Mirrour 2e. London: Nicolas Bourn.

Dafforne, R. (1660). The Merchants Mirrour, 3e. London: Nicholas Bourn.

Geijsbeek, J. B. (1914). Ancient double-entry bookkeeping. Denver, Colorado: Geijsbeek, John B.

Hayashi, Sullivan, R., Weiner, S. E. (2006). A guide to the ATM and debit card industry. Payments System Research Dept. Kansas City: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Little, A. (1975). Consequences of Electronic Funds Transfer. Washington: The Foundation.

Littleton, A.C. (1926). Evolution of the Ledger Account. 1926, 1(4), pp. 12–23. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/239414

Littleton, A. C. (1962). Accounting theory, continuity and change. (V. Kenneth, Ed.) Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Locke, J. (1695). Further considerations concerning raising the value of money, Second Editon. London: A. and J. Churchill.

Nationwide. (2022, May 10). Online Banking Terms and Conditions. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from Nationwide: https://static.nationwide.com/static/Online_Banking_Terms_and_Conditions.pdf?r=65

OED Online. (2022). Oxford University Press. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from http://oed.com

Oldcastle, H., & Mellis, J. (1588). Oldcastle, Mellis, J., & Pacioli, L. (1588). A briefe instruction and maner how to keepe bookes of accompts. London: John Windet.

Sherman, W. R. (1986, October 1). Where’s the “R” in Debit? Sherman. (1986). WHERE’S THE “R” IN DEBIT? The Accounting Historians Journal, 13(2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.2308/0148-4184.13.2.137, 13(2), 137-143. Retrieved from Accounting Information: https://doi.org/10.2308/0148-4184.13.2.137

Thomas, C. W. (2018). Financial Accounting (12th Edition) (Twelfth ed.). Hoboken, NJ, U.S.: Pearson Education. Retrieved from https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/books/9780134727004