Keōua Hale, once located at 21 Emma Street in Honolulu, was a grand Victorian-era palace built by one of the last Kamehameha descendants, Princess Ruth Keelikolani. Keōua Hale, completed in 1882, was

Bernie and Coty Burnfin: How two small-town Americans woke up in a battleship inferno on Dec. 7, 1941

by Jill Byus Radke

If Quarters 31 could talk, it would tell the story of Bernie and Coty Burnfin and how they woke up on December 7, 1941, to a fiery hell in their quiet Belleau Wood Loop neighborhood on Ford Island.

John “Bernie” Burnfin was born in Fristoe, Missouri, in 1903.[i] He left school after the eighth grade[ii] to work on the family farm.[iii] However, the day he turned 18, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy.[iv] Five years later, Bernie married Alta Hagerman in Los Angeles, and [v] about nine months later, they had their daughter, Colleen. The family bounced around rental apartments for several years in southern California while Bernie served on the USS Lexington.[vi]

In 1934, Bernie received his new duty assignment in charge of Navy Recruiting in Chehalis, Washington.[vii] Alta and Colleen did not join him there. He had to go to Washington on his own. He lost his wife, his daughter, and the warmth of southern California all at once. Fortunately, he found a silver lining in Chehalis: he met Coty.

Dakota “Coty” Brengle was born in 1911 in South Dakota and grew up on her family’s ranch, attending country schools like most children in her small town. After graduating from high school and cosmetology school, she moved to Chehalis, Washington, where she opened her beauty shop and school.[viii] During this time, she met Bernie.[ix] They fell in love and married in 1935.[x]

A couple of years later, Bernie was reassigned to Hawaii, prompting Coty to sell her business.[xi] On February 29, 1937, 25-year-old Coty boarded the SS Monterey and sailed across the Pacific Ocean to join Bernie in Hawaii.[xii]

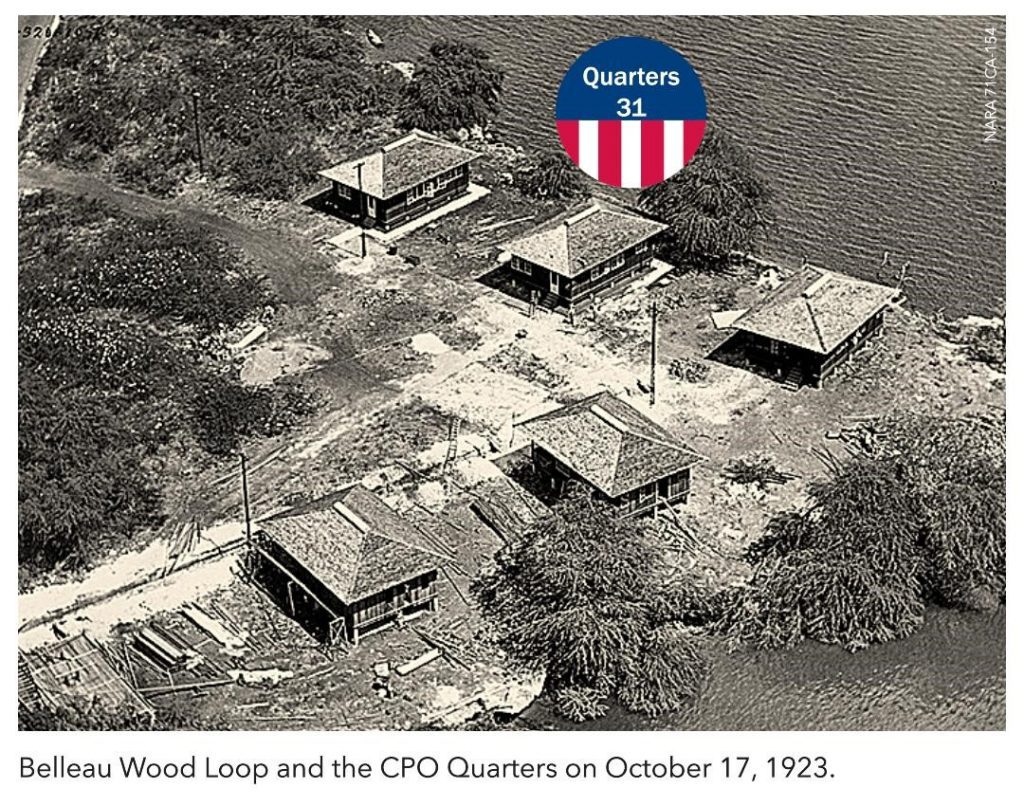

Bernie was a Chief Boatswains Mate at the Naval Air Station on Ford Island, so he and Coty were assigned to Quarters 31 on the Belleau Wood Loop alongside other senior enlisted sailors and their families.[xiii] Their two-bedroom bungalow was not expansive but close to Bernie’s duty station. The house’s views were spectacular —from their back windows, they could see the steel gray fortresses and superstructures of battleship row and the Koolau mountains. Their kitchen and living room windows looked out on the hulls of the USS Maryland and Oklahoma moored nearby.

Coty settled into island life, working at the Pearl Harbor beauty salon, while Bernie served as the fire station chief on Ford Island. [xiv] Their house sat on the northeast side of Ford Island, away from clamoring and engines heard around the hangars and administration buildings. There was no bridge over Pearl Harbor linking Ford Island to the rest of Oahu, so the only traffic to the neighborhood came from the Navy’s ferry system. There were no fences or walls between houses, only canopy trees, open fields, and battleships. Children ran and played in the communal yards of the neighborhood. It was a peaceful, beautiful, and safe place. They fell asleep to the sound of the water lapping up on the coral shore just outside their backdoor.

Coty settled into island life, working at the Pearl Harbor beauty salon, while Bernie served as the fire station chief on Ford Island. [xiv] Their house sat on the northeast side of Ford Island, away from clamoring and engines heard around the hangars and administration buildings. There was no bridge over Pearl Harbor linking Ford Island to the rest of Oahu, so the only traffic to the neighborhood came from the Navy’s ferry system. There were no fences or walls between houses, only canopy trees, open fields, and battleships. Children ran and played in the communal yards of the neighborhood. It was a peaceful, beautiful, and safe place. They fell asleep to the sound of the water lapping up on the coral shore just outside their backdoor.

And then they woke up in a living hell.

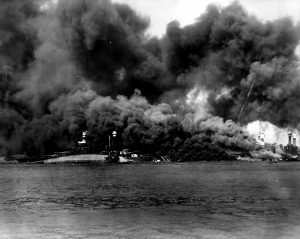

Just before 8 a.m. on December 7, 1941, Lt. Commander Kakuichi Takahashi of Japan led nine dive bombers in an assault on the Pearl Harbor Naval Air Station, dropping bombs on seaplanes clustered around Hangar 6 on Ford Island. [xv] As the seaplane ramps and hangars erupted into chaos, the attack turned toward battleship row.

Ten Japanese Nakajima “Kate” torpedo bombers targeted the battleships moored just a few hundred feet from the Burnfin’s back door.[xvi] Three bombs struck the USS Arizona, causing minor damage. Then bombardier Noboru Kanai dropped a fourth bomb,[xvii] which penetrated five decks below the surface, igniting Arizona’s powder magazine.[xviii] The resulting explosion ripped the battleship apart, causing its forward decks to collapse and lifting the ship briefly out of the water before it plunged back into flames.[xix]

The shockwave from the blast shook the buildings on Ford Island, including Quarters 31, which was just yards away from the explosions.[xx] Bernie quickly jumped into his uniform and bolted out of the house in slippers.[xxi] Coty rushed out of the house and ran across the street to the Kenneth Whiting schoolyard, where she and several neighbors gathered. “You felt like you should find cover somewhere, but there was nowhere to go,” Coty recalled years later.[xxii]

After the first wave of the attack, a truck transported Coty and other family members to Admiral Bellinger’s quarters.[xxiii] They hurried into the basement, which had previously served as Battery Adair. Soon, injured, oil-soaked sailors and marines from the burning battleships began filtering into the basement. Many were so severely injured that the only way Coty knew they weren’t Bernie was by checking their feet for his house slippers.[xxiv]

Meanwhile, still in his slippers, Bernie was busy putting out fires on the southeastern part of Ford Island. He and his team dodged bullets, bombs, and falling debris, successfully saving three planes and barracks from burning.[xxv]

Quarters 31 also survived bullets, bombs, and falling debris. Fragments from the explosions of the ships fell across its roof and yard but fortunately did not catch fire during the attack.[xxvi] Three delayed action bombs intended for the nearby battleships fell, exploded near Quarters 31, and shook the area. Fortunately, they did not cause significant damage to Quarters 31 or its neighbors.[xxvii] Even as the bombs stopped falling, Quarters 31 was still not in the clear.

At 2:30 a.m. on Dec. 8, burning embers from the nearby USS Arizona floated across the Belleau Wood Loop and sparked fires near the CPO quarters and the barracks.[xxviii] Firefighters worked with Bernie to extinguish these fires and others throughout the night. [xxix]

Fortunately, Bernie’s only injuries were blisters sustained from his house slippers.

When Bernie and Coty were reunited, they returned to a home that had survived the United States’ first battle of World War II. Their yard and roof were scorched and littered with burned debris and the wreckage of a Japanese plane.[xxx] The sight of the pilot’s body seared in Coty’s mind the horrors of war. “I’ll never forget him lying there on his back,” Coty said. “He had no shoes on, just gray socks.”[xxxi]

“I was shocked at what I saw. I felt as though I were looking at a scene of children’s toy ships and planes where a ruthless giant had wantonly taken a hammer, smashing everything in sight,” Pearl Harbor Survivor Mildred V. Budny explained.[xxxii]

Three weeks later, Coty evacuated Hawaii and her Ford Island home to spend the rest of the war in South Dakota. Bernie was honored with a letter of commendation from the President for acts of valor during the attack on Pearl Harbor.[xxxiii] He continued to serve in the U.S. Navy and retired after 30 years. He and Coty operated hotels and properties in Missouri until Bernie died in 1982.[xxxiv] After Bernie’s death, Coty returned to Rapid City, South Dakota, where she lived until she died in 2010.[xxxv]

Bernie and Coty’s Ford Island home survives as a tangible reminder of the struggles that Coty, Bernie, and other military families overcame during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Unlike the somberness you experience at the adjacent memorials, standing on the steps of Quarters 31 in the shadow of the massive guns of the Battleship Missouri, people can feel the vulnerability Coty and Bernie must have felt on Dec. 7, 1941. This small bungalow with battenboard siding and a shingled roof provided little shelter from the armor-piercing bombs that fell nearby. Without hearing or reading a word, visitors can experience where the harsh realities of war met the peaceful lives of families in one shocking moment of surprise. The nearby memorials list the names of the men who died in the attack, but the historic homes of Ford Island tell the stories of the families who survived that horror and lived with those haunting memories for life.

Author’s Note

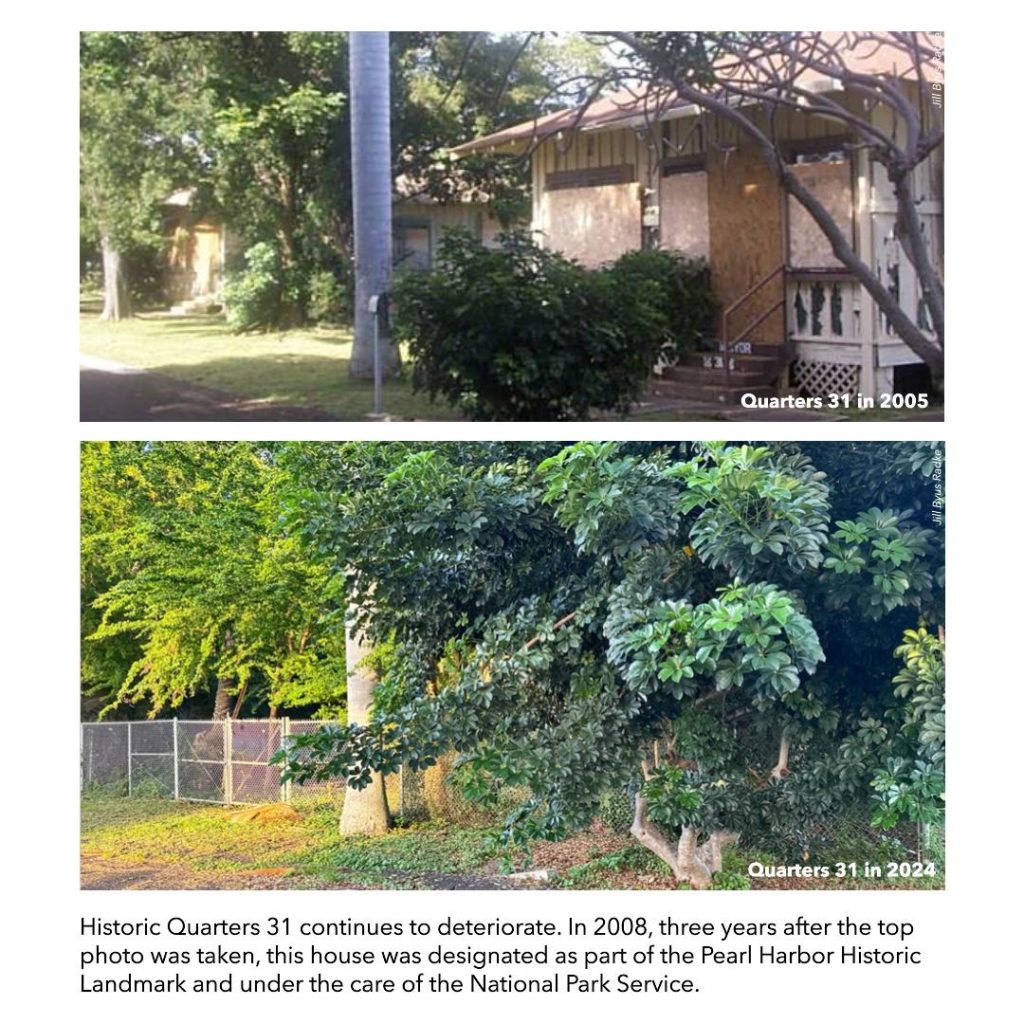

Though the bombs and debris have dissipated, Quarters 31 is fighting a brutal battle to survive. A 1987 survey of military homes recommended it for demolition and removal from the housing inventory because it “did not meet the minimum net square footage for US Army family housing.”[xxxvi]

In the 1990s, the last family moved out of Quarters 31 and the other CPO Bungalows on Belleau Wood Loop. They sat vacant without maintenance until they were designated as part of the Pearl Harbor National Memorial by a Presidential Proclamation in 2008.[xxxvii] From 2009 through 2012, the National Park Service provided emergency care, such as fumigating for termites and stabilizing the structural foundations.[xxxviii]

In 2015, the National Park Service demolished Quarters 28 and constructed a new structure in its place.[xxxix] Quarters 31 remains in poor condition, with vegetation quickly overcoming its wood construction.

Sources Cited

331 Persons Honored By Navy for Deeds of Valor. (1942, April 6). Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7.

1920 United States Federal Census — Ancestry.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4312390-00466?pId=57235311

1930 United States Federal Census—Ancestry.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/6224/records/89978025?tid=13106928&pid=402622370356&hid=1032681171055&usePUBJs=true

1940 United States Federal Census—Ancestry.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/M-T0627-04586-00739?pId=78937074

A Piercing Blow: The Aerial Attack on the USS Arizona. (n.d.). Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum. Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.pearlharboraviationmuseum.org/visit/experiences/piercing-blow-aerial-attack/

Ancestry.com—California, U.S., County Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1849-1980. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61460/images/47732_B354060-00160?treeid=13106928&personid=402622370356&hintid=1032681171059&usePUB=true&_phsrc=TTg912&_phstart=default&usePUBJs=true&showinfopanel=true&pId=900763437

Budny, M. F. (2002). I Wish I Weren’t Going to Have This Baby: A US Navy Wife Remembers Pearl Harbor. Hawaiian Journal of History, 36(155).

Cultural Landscapes Inventory Ford Island CPO Bungalows Neighborhood and Battleship Row. (2020). National Park Service.

Dakota “Coty” Brengle Burnfin (1911-2010)—Find… (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/54995943/dakota-burnfin

Fleet Intelligence Center Pacific. (n.d.). Aloha! History of Ford Island.

Goldstein, D. (1995). The Way It Was: Pearl Harbor. Brassey’s.

Harlan, B. (1991, December 7). Nowhere to hide during bombings. Rapid CIty Journal, 6.

Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S., Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1900-1959—Ancestry.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/records?recordId=624684&collectionId=1502&tid=13106928&pid=402622370326&queryId=44f63324-a5fe-425d-9594-963de733b0f0&_phsrc=TTg937&_phstart=successSource

Jack Rogovsky Collection. (n.d.). [Online text]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2001001.105973/

John Burnfin (1903-1982)—Find a Grave Memorial. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6053041/john-burnfin

Mariani and Associates. (1987). Study/Survey of Historically Significant US Army Family Housing Quarters, Installation Report, Mariani and Associates, (p. 169). Pearl Harbor Naval Base, Hawaiʻi.

Obituary for Dakota Coty Burnfin at Kline Funeral Chapel. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://www.klinefuneralchapel.com/obituary/646520?lud=E1A3BF2C4B6CB74B6AC6FA85FC0B4477

U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995—Ancestry.com. (n.d.). Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/records?recordId=735829374&collectionId=2469&tid=&pid=&queryId=bc1812e7-e86c-4924-858b-949957393fed&_phsrc=TTg1004&_phstart=successSource

End Notes

[i] (John Burnfin (1903-1982) – Find a Grave Memorial, n.d.)

[ii](1940 United States Federal Census, n.d.)

[iii] (1920 United States Federal Census, n.d.)

[iv] (John Burnfin (1903-1982) – Find a Grave Memorial, n.d.)

[v] (Ancestry.Com – California, U.S., County Birth, Marriage, and Death Records, 1849-1980, n.d.)

[vi] (1930 United States Federal Census – Ancestry.Com, n.d.)

[vii] (U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 – (Ancestry.Com, n.d.) (John Burnfin – Find a Grave Memorial, n.d.)

[viii] (Dakota “Coty” Brengle Burnfin (1911-2010) – Find…, n.d.)

[ix] (1940 U.S. Census)

[x](John Burnfin (1903-1982) – Find a Grave Memorial, n.d.)

[xi](Dakota “Coty” Brengle Burnfin (1911-2010) – Find…, n.d.).

[xii](Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S., Arriving and Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1900-1959 – Ancestry.Com, n.d.) (Harlan, 1991)

[xiii] (Harlan, 1991)

[xiv] (1940 U.S. Census) (Harlan, 1991)

[xv] (Goldstein, 1995)

[xvi](A Piercing Blow, n.d.)

[xvii](Goldstein, 1995)

[xviii](A Piercing Blow, n.d.)

[xix] (Goldstein, 1995)

[xx](Jack Rogovsky Collection, n.d.)

[xxi] (Harlan, 1991)

[xxii] (Harlan, 1991)

[xxiii] (Harlan, 1991)

[xxiv](ibid)

[xxv] (“331 Persons Honored By Navy for Deeds of Valor,” 1942)

[xxvi] (Fleet Intelligence Center Pacific, n.d.)

[xxvii] (Ibid)

[xxviii] (Ibid)

[xxix] (“331 Persons Honored By Navy for Deeds of Valor,” 1942)

[xxx] (Harlan, 1991)

[xxxi](Ibid)

[xxxii](Budny, 2002)

[xxxiii](“331 Persons Honored By Navy for Deeds of Valor,” 1942)

[xxxiv](Obituary for Dakota Coty Burnfin at Kline Funeral Chapel, n.d.)

[xxxv] (Ibid)

[xxxvi](Mariani & Associates, 1987)

[xxxvii](Cultural Landscapes Inventory Ford Island CPO Bungalows Neighborhood and Battleship Row, 2020)

[xxxviii] (Ibid, p. 31)

[xxxix] (Ibid, p. 31)

Related Posts

The History of Ford Island: From Oysters to Ships

The story of Pearl Harbor and Ford Island cannot be separated from its role in the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. This brief history goes over the basics of how a body of water that once fed the

One for All: The Many Reasons to Love OC1s

Dozens of one-paddler outrigger canoes (OC1s) drift side-by-side at the racing start line several yards off Lanikai Beach in Hawaii. My canoe and I are sandwiched between a teenager with Justin Bieber